The Idea and Practice of Smart Cities in India

The past is often used to keep non-western cultures and civilizations in a vice-like grip and it comes from imposing limits on vision for the future. We have to define our own culture in terms of our own categories and concepts and to articulate our vision in a language that is true to our self.

In the unique culture of India, there are informal rules operating at the State/city levels. The work of Nobel Laureate Elinor Ostrom provides some useful insights into the informal rules driving local level actions. In her study of mechanisms of self-governance operating in the less-developed world, Ostrom found that decentralized groups develop various rule systems that enable social cooperation to emerge through voluntary association. She investigated situations where rules for dividing property into private plots do not exist. In such cases she found that non-State decision-making follows “rules in use” and accomplishes what the State mandated “rules in form” would have accomplished. In the context of policy-making rules in form represent the Government policy and the rules in use are the informal norms followed by non-state actors and entities at the ground level.

Such “calculated informality “ _ _ _ involves purposive action and planning _ _ _ where the seeming withdrawal of regulatory power creates a logic of resource allocation, accumulation and authority _ _ _ in this sense that informality, while a system of deregulation, can be thought of as a mode of regulation. And this is something quite distinct from the failure of planning (decision-making) or the absence of the state”. In these informal settings, a one-size-fits-all policy often leads to unintended and uncertain outcomes on ground and is one of the main reasons for the gap between policy and execution.

The outcomes of the interaction between the rules in form and rules in use are difficult to predict because the rules in use are specific to time and place and tacit – hard to write down, not obvious to frame. As a result, some policies may be implemented as stated, others may not be used as stated or policies may go by one name, but in practice do something else. The overall effect is that policies remain formal in appearance, but play out differently during implementation.

In order to minimize the mismatch between the rules in form and rules in use, policies have to strike the right balance between allowing rules in use to operate without opening the door to discrimination, lack of openness, corruption and arbitrariness which formal rules in form are supposed to prevent. In other words, a mix of bottom up and top down approaches is likely provide greater scope for freedom of action and thought to the local rules in use leading to a closer fit between rules in form and rules in use during implementation. The Smart Cities Mission (SCM; henceforth called Mission) blends bottom up and top down approaches by designing a ‘loose fit’ Mission (rules in form).

Defining Smart Cities

A smart city has a different connotation in India than, say, Europe. Even in India a smart city means different things to different people and the conceptualization of a smart city varies from city to city, state to state and region to region, depending on the level of development, willingness to change and reform, resources and aspirations of the city residents. No single definition can capture the diverse conceptualizations of city residents, especially in the unique Indian culture containing dynamic, diverse and contextual rules in use.

One way to capture the varying conceptualizations is to allow the residents to have a say in policy formulation and execution by prescribing flexible, broad policies in the form definitional boundaries within which residents can influence local policies and their implementation. Once local rules in use are given importance, “people will assume ownership of projects and leave no stone unturned to make the Mission successful”. Such definitional boundaries will permit policy making by citizens within some overarching goals and an overall strategy. The Mission fixed the following broad goals and strategy.

- Objective: To promote cities that provide core infrastructure and give a decent quality of life to its citizens, a clean and sustainable environment and application of IT enabled smart solutions.

- Strategy: Apply smart solutions to improve governance and public services and make the city smart through area-based development.

Holistic Development

To provide for the aspirations and needs of the citizens urban planners ideally aim to develop all elements contained in the institutional, physical, social and economic infrastructure. This can be a long-term goal and cities can work towards such holistic development, incrementally, by adding on layers of ‘smartness’. The Mission consists of three layers of smartness:

First layer: Provides citywide core infrastructure (basic services and physical infrastructure) to provide for the basic needs of the residents. This is the first layer of the smart city and some of the elements are given below.

- Adequate and clean water supply,

- Assured electricity supply,

- Sanitation facilities, including and solid waste management,

- Efficient urban mobility and public transport,

- Affordable housing, especially for the poor,

- Robust IT connectivity and digitalization,

- Good governance, especially. e-Governance and citizen participation,

- Sustainable environment,

- Safety and security of citizens, particularly women, children and the elderly, and

- Health and education.

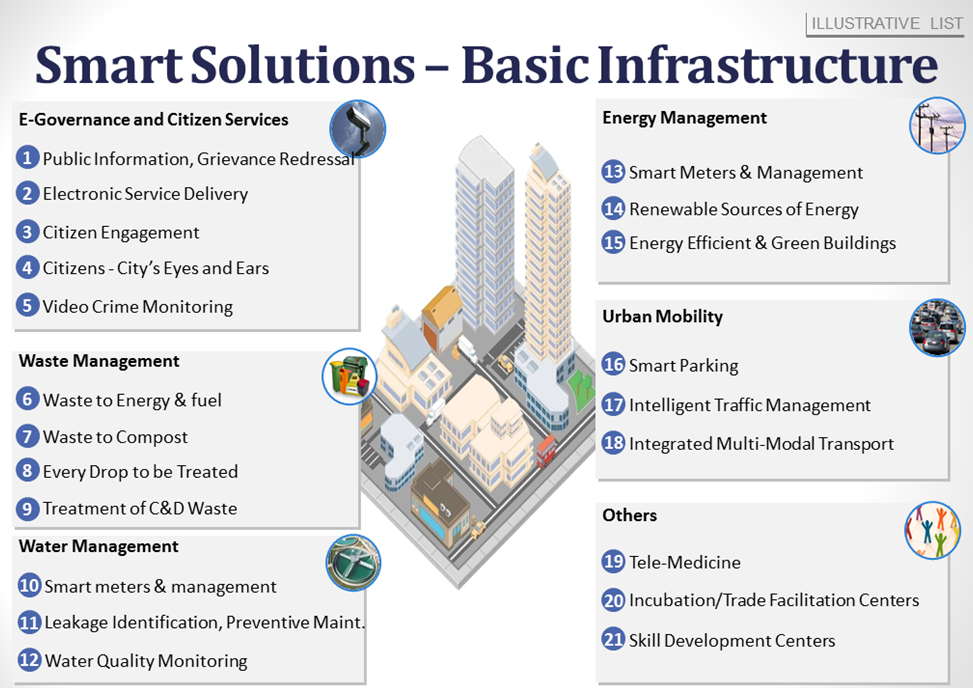

Second layer: Consists of application of smart solutions to infrastructure and services to improve them. This is done at the citywide (pan-city) and an illustrative list of smart solutions is given in Figure 1. Application of smart solutions to existing infrastructure and services is expected to, (1) extract more output from the existing assets and resources, (2) use less resources to deliver the same output and, (3) improve governance and delivery of public services.

Figure 1. Illustrative list of smart solutions

Third layer: This consists of development of all elements in compact parts of the city, called ‘Areas’ (also called area-based developments and used interchangeably). Such Areas act as a Lighthouse for other Areas in the City to emulate and develop over time. Box 1 gives the strategic components of area-based developments in the mission.

- Retrofitting will completely develop an existing built area of more than 500acres so as to achieve Smart City objectives, along with other objectives of making the existing area more efficient and livable.

- Redevelopment will replace the existing built environment in an area greater than 50 acres and enable co-creation of a new layout, especially enhanced infrastructure, mixed land use and increased density.

- Greenfield developments will completely develop a previously vacant area, of more than 250 acres, using innovative planning, plan financing and plan implementation tools with provision for affordable housing, especially for the poor.

The negative effects of congestion forces can be reduced by appropriately integrating the elements in the Areas, such as land-use, walkability, last-mile transport, affordable housing, open spaces, open space of all types – parks, playgrounds and recreational – and usage of information technology to improve services and infrastructure. At the same time Smart Solutions can be applied at the city level to realize the full

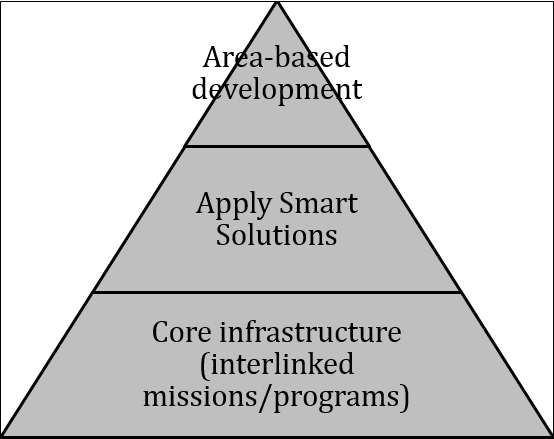

The three layers, and their elements are complementary and overlapping and can be represented as three layers contained within a triangle (Figure 2). The basic building block is the provision of core infrastructure to meet the basic needs of all the city residents, particularly the poor and the disadvantaged. Next, smart solutions are applied to core infrastructure and services in order to improve the life of all its residents. On the top is area-based development in which Areas are made more livable, for example, by creating walkable localities, promoting mixed land use and a variety of transport options, providing housing for all and preserving/developing open spaces. This in a nutshell is the idea and practice of integrated planning in the India Smart Cities Mission, which leads to holistic development in the long run.

Figure 2. Integrated planning triangle

The Competition

The focus of the Mission is on making people part of the policy formulation and partners in execution. The local policy and implementation is articulated in the form of a Smart City Proposal (also called Plan and used interchangeably) and generated through a process of competition, perhaps for the first time for a public program of this size. The winners of the Challenge (process of competition) get funding to become smart cities. The Challenge consists of a two-stage competition. The States conduct the Stage 1 of the intra-state competition and in Round 1 led to shortlisting of 100 cities (also called potential smart cities). In Stage 2 the Central (Federal) Government organized an All-India competition. The uniqueness of the potential smart city was captured by the Proposal – the deliverable of the Stage 2 of the competition.

The Challenge helped the city residents to gather thoughts and ideas towards defining their smart city, and innovative approaches towards how these can be implemented based on the local context. Key stakeholders were involved quite early on in the planning and saw themselves as partners in the process of building cities. This led to high levels of citizen engagement and involvement of other stakeholders, such as specialists, technical experts, professionals, private players and political representatives.

The content of the Proposal was the competition brief, which was to be submitted to the Government of India by the potential smart cities. The Proposal required that each city should propose to develop one area-based development – either a retrofitting of minimum 500 acres, a redevelopment of minimum 50 acres or a Greenfield development of minimum 250 acres – on the principles of place-making and apply one or two pan-city smart solutions, which would improve the quality of life and/or the delivery of municipal services throughout the city.

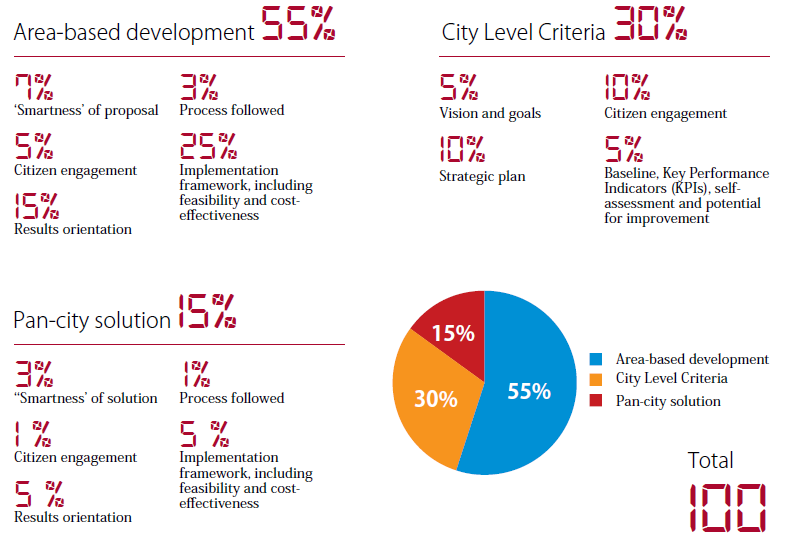

A standard template was devised for submission of the Proposals, such that all Proposals, regardless of the size and type of city, could be judged on a common basis and on their own merit. A unique innovation was introduced through the design of the blank standard template in which the Proposals were to be prepared, consisting of a set of 43 questions and providing limited word counts for each response as well as a stipulation of page limits for enclosures. The 43 questions were divided into three broad categories – city-level vision, goals and strategy, area-based development and pan-city smart solutions. Figure 3 gives the details of the scores given to different sub-criteria in the Proposal.

Figure 3. Scoring criteria/sub-criteria for three categories in the Proposal

Integrated Planning: The Proposal

The Proposal was prepared using principles of integrated planning involving extensive citizen consultations at multiple stages. The strategic part of the Proposal contained the way infrastructure elements in layers would be gradually implemented to cover the full city in the long-run and the tactical part contained concrete and well phased plans that were easily implementable.

At the city level – strategic blueprint

The city strategy determines the elements to be included in the layers and their sequence of implementation. The strategic blueprint consists of a pathway to make the entire city smart by gradually (incrementally) developing,

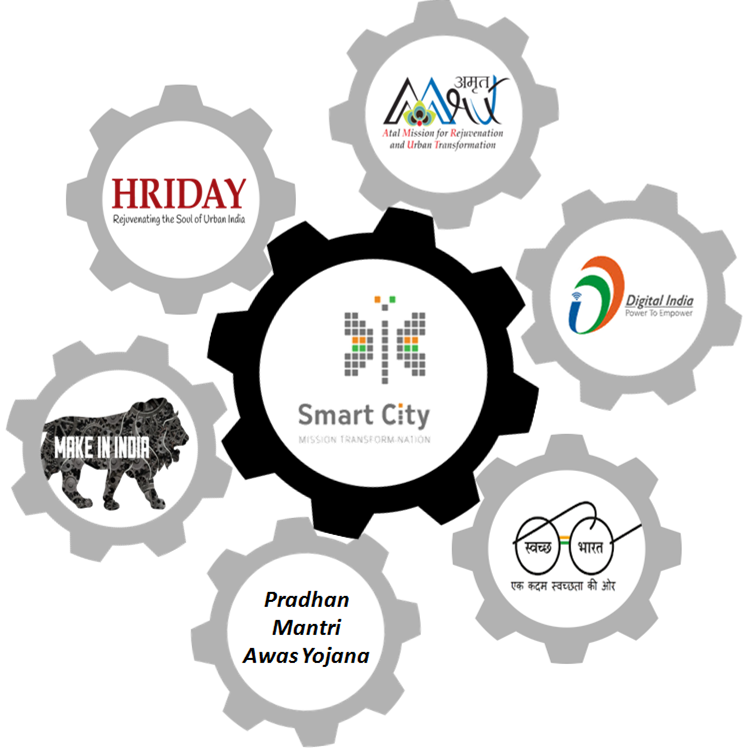

- Core infrastructure – in order to prepare the entire city to become smart, many of the sectoral schemes of the government converge in the goal of the Mission. Figure 4 gives some of the interlocked programs around the Smart City Mission, which have the potential to be converged in the Proposal.

- There is a strong complementary between the Atal Mission for Rejuvenation and Urban Transformation (AMRUT) and the Smart Cities Mission, such as to improve governance, sanitation, water-supply, waste management, urban mobility and other such urban infrastructure projects at the Pan-city level.

- Similarly, other programs/schemes of the Central and State Government can be converged. At the planning stage itself such convergence can be achieved in the Proposal with Swachh Bharat Mission (SBM), National Heritage City Development and Augmentation Yojana (HRIDAY), Digital India, Skill India and other programs connected to social infrastructure, such as health, education and culture,

- Replicating area-based developments – one Area is selected in close consultation with citizens. For this, the entire city is divided into Areas and the strategy indicates how all these Areas would be developed one-by-one to cover the entire city over time, and

- Applying one or two smart cities initially and gradually adding more and more IT-enabled smart solutions at the pan-city level.

Ideally, the three layers are implemented one after the other starting by addressing the basic needs of the residents, first. However, some cities can apply smart solutions during the development of core infrastructure and, thereby, leapfrog one stage. Another way to leapfrog is to apply smart solutions without waiting for the upgradation of the existing city infrastructure and services.

Figure 4. Dovetailing of interlocked programs around the smart city mission

At the sub-city level – tactical plan

The tactical plan integrated various aspects of the Proposal, such as delineation of project boundaries of a contiguous Area, selection of type of area-based development (retrofitting, redevelopment, greenfield); application of smart urban form to the Area, mixed land use, transit-oriented development; use of IT to improve systems and delivery; place-making and planning for complete development of the Area. The process followed by the cities was given significant weightage in the evaluation, with citizen involvement and stakeholder consultations forming the bedrock of the smart city tactical plan.

The results orientation and ‘do-ability’ of the proposal was another significant part of the tactical plan. The scoring criteria given in Figure 3 shows that nearly 30 percent of the marks were given for implementation framework and feasibility. The feasibility of the implementation of the proposed developments could be understood as the result of maximum convergence of funds from Government sources, leveraging of private investment, public private partnership frameworks for sustainability and the assessment of risks and mitigation measures required.

The Proposal conceived in this way led to replacement of top-down processes, tools and tactics with a more bottom-up approach. There was a greater focus on bottom-up self-organization and collaboration in order to capture the rules in use – direct and indirect, explicit and implicit, tacit and obvious. The Proposal was generated through a detailed process containing several types of feedbacks from the citizens (e.g. discussion forums, polls, blogs, suggestions). The involvement of different stakeholders was a measure of the integrated planning and evidence-based planning. What emerged finally was an admixture of bottom up and top down approaches.

SPV: Bridging the Implementation Gap

The dynamic interplay between rules in form and rules in use generates an ever-changing relationship between the two. As a result, rules in form are rendered open and the uncertainty and ambiguity so generated adversely affects decision-making leading to delays in execution.

One way to bridge the execution gap is to create an entity, which is autonomous, able to quickly adapt to rules in use, regulated by some basic, inviolable rules in form and accountable to the municipal representatives. The Mission proposed that in each smart city a company would be established at the city-level owned by the State Government and the City, governed by the regulations of the Companies Law and managed by professionals. In India, companies (corporations) have been formed at the State level, not at the municipal level. Other countries, such as China and Africa have formed companies at the city level to access investments and develop urban infrastructure. Box 2 gives the details of the companies established by China and Africa.

In the Mission, therefore, implementation of projects is done by a city-level Special Purpose Vehicles (SPV). The SPVs are permitted to enter into joint ventures with other entities to raise capital. These will be autonomous bodies accountable to the city, with majority ownership held by the State/City and the private sector and financial institutions could hold minority equity stakes.

- Financing platform. UDICs raise funds for urban infrastructure development from multiple channels. They provide borrowed money to infrastructure projects through on-lending or direct investments.

- Public sector investor. UDICs operate as authorized investment agents of the municipal government or state-owned asset administration authorities. UDICs operate and manage the assets within their authorized scope and are responsible for maintaining the value of the asset and protecting the interests of the government.

- Land development agent. Many UDICs conduct up-front development and management of land allocated by local government in urban planning areas.

- Project sponsor/owner. UDICs sponsor and own priority urban infrastructure projects. In this respect, UDICs are

Their involvement in social infrastructure varies form local government to local government. According to one estimate there are nearly 360 established UDICs with varying operational models and reporting structures. The results have been impressive. Infrastructure investment has been maintained at approximately 9-10 percent of the GDP. The level of infrastructure investment, as well as the quality of infrastructure in China compares favourably in the regional and global context.

In South Africa, Municipal Entities (ME) are set up to manage and develop specific services, sectors or portfolios. They are separate companies normally wholly owned by the municipality (thought this is not mandatory and municipalities may hold a partial interest in a company if the other shareholders are national/provincial government or, if it’s a private sector company, the municipality has a controlling interest) and regulated by one of its departments. While they may issue debt, this is tightly regulated and they are not primary vehicles for raising (off balance sheet) debt finance for general urban development purposes (which is what SPVs normally are – as in China). In S. Africa there were 91 municipal entities in 2006. Municipal entities have been utilized to perform a variety of functions. The developmental and planning function includes economic and business development (excluding tourism) with 21 entities represented. This is followed by housing services with 11 entities and water services with 6 entities. Of the 91 municipal entities, 41 entities were companies followed by 31 private companies, 6 trusts and 5 service utilities.

Sameer Sharma,

Additional Secretary(Smart Cities),

Ministry of Urban Development

Disclaimer – All views are personal