Manipur’s Thongjao Pottery

The residents of Thongjao Village in Thoubal District of Manipur are considered to be ancient pottery makers. They are believed to have migrated from Thongjaorok in Lamangdong, Bishnupur district 500 years ago.

Pottery is a primary occupation of the village. It is mostly practiced by women without using a potter’s wheel.

It is worth noting that Manipur’s social, cultural, and religious life are all strongly entwined with pottery. Traditionally, Meitei pottery is made by coiling strands of clay into an array of shapes and sizes without using a spinning wheel.

The distinguishing feature of Thongjao pottery is its scarlet tan colour. It is mostly made by women using slabbing and shaping techniques. The perfectly striated neck sherd is produced using hands, which can be easily mistaken for a wheel-made striation.

Different types of pots are made depending on the purpose: Pun (water pots), Kharung (Liquor pots), Chengphu (rice pot), Khujai (water pot), Isaiphu (water jar), Sanabun (water pot), Ngari Kharung (dry fish seasoning earthen pot), Hidak Phu (Hookah), and many others.

Process of Making Thongjao Pottery

The raw materials of the pottery are collected from a nearby pond.

The clay known as Leitan Leimu (in the Meitei language), is dug up from pits 10 feet deep.

The Leimu is then proportionately mixed with a whitish clay known as Leikok and highly winnowed sand locally known as Nungjreng.

The prepared clay is kneaded and rolled into a required coil depending on the size of the pot to be prepared.

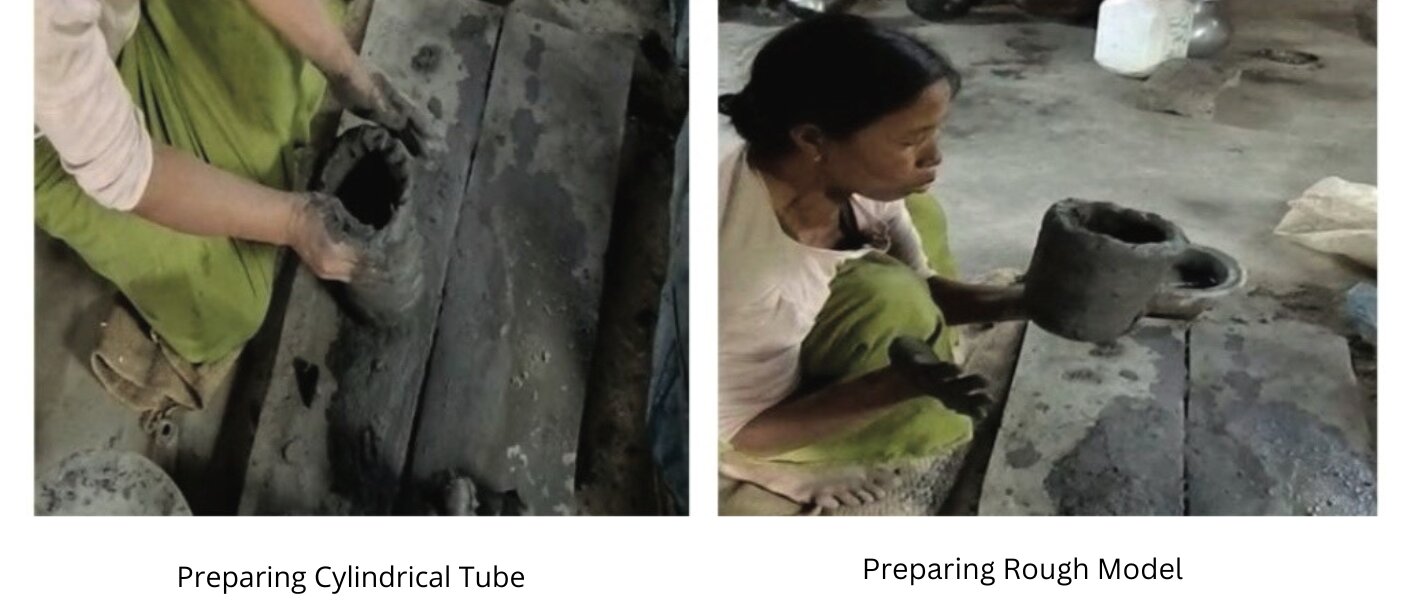

The coil is flattened and smoothened by pressing with the potter’s thump to make it into a thick slab. The clay slab is set upright around a circular clay piece that forms the base, resulting in a cylindrical tube.

The roughly shaped pot is mounded on an hourglass-shaped wooden stand known as legsum.

A wet rag called ngabong phi and fingers is used to make the rim and the neck of the pot.

The rough model is taken on the lap and beaten with a rectangular-shaped beater ‘Phujae’. The beating is done from the outside, with the anvil kept within.

This process should be in a synchronistic manner to maintain a balance from both surfaces failing which the shape of the pot will be deformed. The entire shape of the pot’s body is created in this manner.

Polishing and Decoration

Bamboo split, shell, or Kang are used to burnish the pottery.

Floral and other geometrical designs are dabbed on the damped models with incised wooden beaters known as Phujae.

Bivalve shells or Kongreng (oyster) and Kang, a seed of Entada phaseoloides, are rubbed on the pots outside surface to create decorative shiny polished marks. Typically, a pot’s shoulder is where you’ll find this polish mark.

After decoration, the pots are left in the shed for four or five days for drying. During monsoon season, more days are required.

Pottery Firing

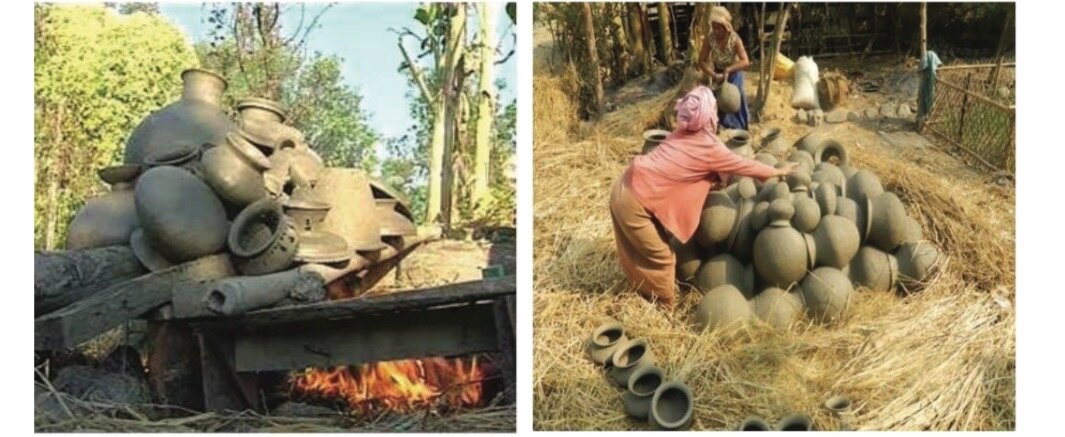

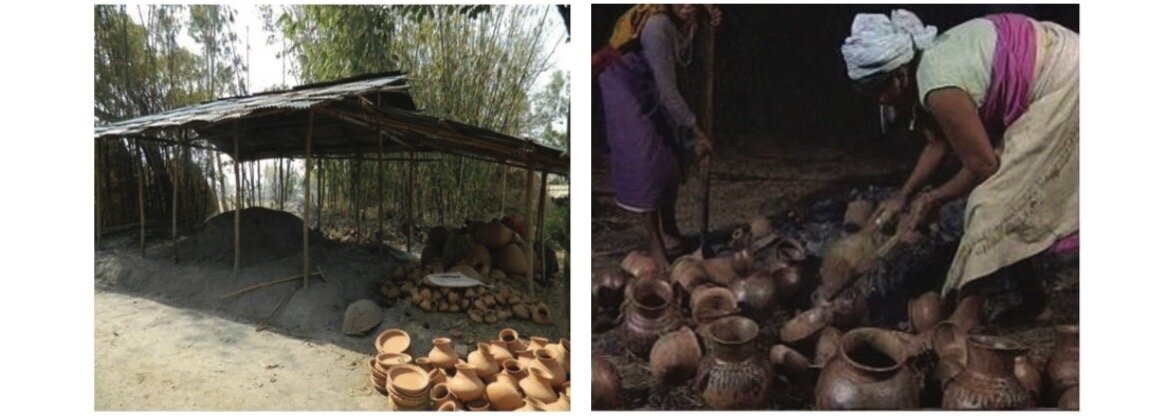

Pottery is fired on a bamboo platform before being moved to a proper kiln for a complete firing. The Thongjao kiln is constructed of bamboo pillars that are open on all sides.

The pottery is then moved to a kiln for the final fire stage, where they are staked over a bed of bamboo and blanketed with layers upon layers of slowly burning rice husks. The pots are arranged in such a way that there is no space left between them.

The final layer is made up of bundles of paddy straw, which is followed by ash to create a mound. The fire is then started at the base and left unattended for over two days.

When the kiln is completely smoke-free, only then the pots are carefully removed with a tong and sometimes sprinkled with Pasania pachyphyla’s kuhi solution using a reed brush.

The bark of the kuhi tree is soaked in water for roughly five days to create this solution. This is used to give strength and colour to the pot.

Transportation to the Market

Because the pots are so delicate, they are meticulously wrapped in jute bags and bundles of straws to keep them perfectly compact, and a truck or a mini truck is used to transport them to marketplaces like the famous Ima Keithel in Imphal so that they can be sold there.

At the market, the pots are organized in columns by carefully stacking each pot on top of the previous one.

Although there is still a demand for plain-looking pots since they play a significant role in Manipuri culture in religious and marriage ceremonies, some potters are focusing on creating new modern, creative designs and models to attract potential buyers other than their regular customers.

Master Potter of Manipur from Thongjao: Naorem Neelamani Devi

Neelamani Devi, born on September 1, 1938, in Thongjao Keithel Leikai, Thoubal District is an Indian craftswoman and master potter who was awarded the fourth highest civilian honor of the Padma Shri by the Government of India, in 2007, for her contributions to the art of pottery making.

In recognition of her artistry in pottery, two documentary films were produced: ‘Mittee aur Manab’ in 1986 by renowned film director Mani Kaul, and Nilamani: The Master Potter of Manipur, in 2003 by renowned Manipuri Film Director, Aribam Shyam Sharma.

Her pottery creations were featured in one episode of the Indian Television series Mahabharata and the first three episodes of the Mahabharata TV series made by French Television.

The details of her work have also been documented in print in a book, Other Masters: Five Contemporary Folk and Tribal Artists of India, published in 1998 by the Handicrafts and Handlooms Exports Corporation of India.

She established the Pottery Training Cum Production Centre in 1966, where she trained a large number of neighbourhood women, while also helping them in earning their livelihoods.

She has travelled extensively for this purpose and has also displayed her artwork in India and abroad.

She has received other awards as well, including the 1986 Tulsi Samman Award and the National Award for Master Craftsman. She also received the Samaj Kalyan Seva Award and the Lions Karmayogi Award in 2005-2006.

References:

- Padmashree Awardee-2007 in the field of Pottery. E-pao

- Thongjao- A perspective of Ethnoarchaeology